Companies pause frantic fundraising to assess pandemic damage

Companies are pausing for breath after a frantic four-month race to secure cash, drawing down bank credit lines, agreeing government rescue financings and issuing new debt and equity to outlast the coronavirus crisis.

The frenetic pace of fundraising, which set records in debt and equity markets, provided much-needed money to airlines such as American and United, cruise operators Carnival and Norwegian and carmakers Ford and General Motors. It was a sudden inflow that helped prevent a big rise in corporate failures, at least for the moment.

Bankers say companies are now assessing the damage wrought by the crisis and waiting before they borrow more, even as debt markets remain wide open.

Padded by the extra cash, companies raised just $70bn last week through debt markets, the lowest since mid-March when the coronavirus crisis sent stock and bond prices tumbling. US issuance dropped to just over $5bn in the holiday-shortened week, according to data provider Refinitiv.

The slowdown follows the most intense burst of capital raising in history, with about $5.4tn secured by companies across the globe since the year began, including $3.9tn since the start of March.

“Companies have been taking insurance policies out, not knowing the depth or length of the recession,” said Kevin Foley, who heads debt capital markets at JPMorgan Chase. He added that some of the groups had assumed lockdowns could persist for a year or longer, which is why several companies moved to raise cash multiple times since March.

Historic backstop measures from the Federal Reserve in March paved the way for companies to load up on debt, as the US central bank appeared to disregard its earlier warnings of rising corporate leverage and deteriorating lending standards.

Borrowing costs for high-grade companies, which hit the highest level in more than a decade in March as investors prepared for a wave of defaults, declined swiftly after the Fed moved to backstop the $10tn US corporate bond market. Government interventions also softened the blow, with stimulus measures helping lift consumer spending and shore up confidence in markets.

Along with rescue financings for the likes of Boeing, blue-chip companies including Walt Disney, JPMorgan and AT&T borrowed billions of dollars through debt markets. Others such as US regional bank PNC Financial and telecoms-to-technology group SoftBank raised cash by selling stakes in non-core units. For PNC it was a $13.3bn position in asset manager BlackRock, while SoftBank sold off $15.9bn of stock in T-Mobile.

“Investment grade companies have the luxury of being able to say, ‘Here I’ll [raise] too much liquidity,’” Mr Foley said. “No CFO was ever fired for having a mentality of [securing] too much liquidity.”

The rebound in markets allowed a long list of companies to lock in their lowest ever borrowing costs, including ecommerce behemoth Amazon and drugmaker Pfizer. Groups in the eye of the storm such as United Airlines and Carnival, meanwhile, were able to secure funds by pledging assets. That collateral, which included aircraft, ships, islands and rewards programmes, helped entice creditors even as rating agencies warned that the risk to lend to the vast majority of companies had increased.

Some advisers such as Roxane Reardon, a partner at law firm Simpson Thacher, have tempered their expectations of how much more debt can feasibly be borrowed this year, given that discouraging outlook.

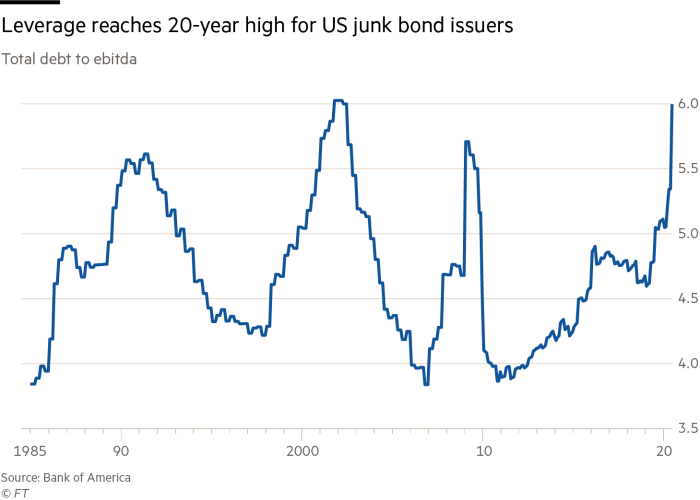

Analysts at Bank of America note that leverage in the US high-yield bond market has already surpassed levels seen during the 2008 financial crisis — in terms of the ratio of companies’ gross debt to their earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation — and is fast approaching levels last seen in the early 2000s. That is causing credit rating agencies to express concerns.

“At some point the capital structure becomes too leveraged and that’s where the rating agencies say, ‘do liquidity first so we don’t have to worry about it going away . . . but then let’s wait for the cash flows to pay down debt,’” said John Chirico, co-head of North American banking and capital markets at Citigroup.

Many companies have already hit the wall. Corporate America has experienced a spate of bankruptcies, as companies in the energy and retail sectors have been shut out from capital markets. Groups such as shale producer Chesapeake, mid-market family restaurant chain Chuck E Cheese and Canadian circus act Cirque du Soleil are now attempting to restructure their businesses under bankruptcy protection.

But advisers and investors have cautioned that many of the companies pushed over the edge were already struggling with high debt burdens before the crisis.

“There’s still uncertainty over where this goes; everybody wishes they had a crystal ball,” said Ms Reardon. “But people have a sense that they are more confident in how they are going to manage it and how the markets are going to respond.”