Diamond sector grinds to halt as India’s lockdown bites

When Indian prime minister Narendra Modi ordered a national lockdown last month in response to the global coronavirus pandemic, Surat suffered an exodus as migrant labourers fled from urban areas to their rural hometowns.

The city, one of the world’s fastest-growing, is the global hub of diamond manufacturing. Ninety per cent of all diamond cutting and polishing is done in India, mostly by artisans in Surat.

But with no stones left to cut, many of these people left. About 200,000 diamond workers have departed to towns and villages in the surrounding state of Gujarat, according to Dinesh Navadia, head of the local industry association, as the global industry ground to a halt.

“We need India to open up,” said Stuart Brown, chief executive of Canadian miner Mountain Province Diamonds. “Until the manufacturing opens up there, there will be no demand for rough diamonds.”

The south Asian country has in recent decades cemented its status as the global industry’s indispensable middleman, buying up rough diamonds mined by the likes of De Beers in southern Africa and Russia’s Alrosa and pumping out polished gemstones or finished jewellery for sale in the US, China and across the world.

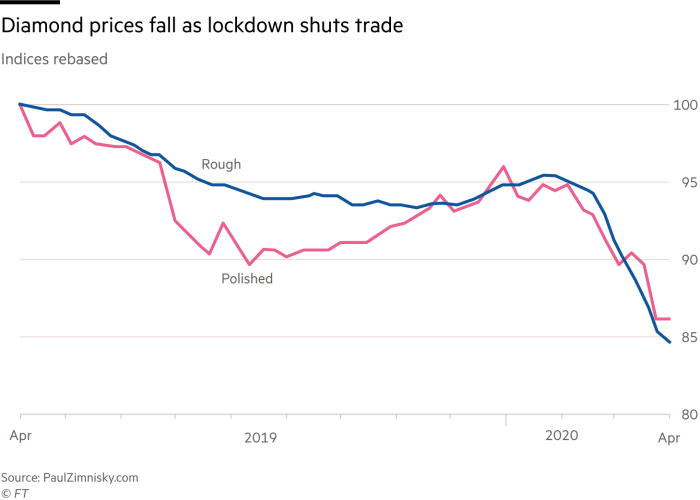

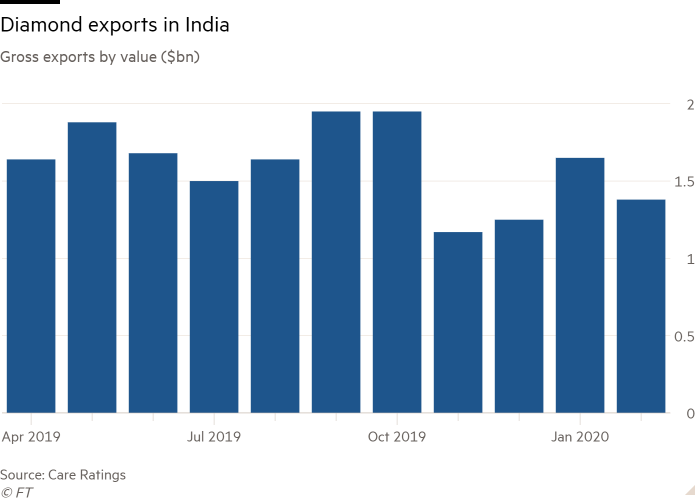

Dependence on India was already proving troublesome for global market leaders such as De Beers and Rio Tinto because of a local economic slowdown and funding squeeze, prompting a drop in imports and exports while forcing miners to cut rough diamond prices.

Now Mr Modi’s abrupt decision has brought the problem into even sharper focus, as the standstill highlights the fragility of the industry’s fragmented supply chain.

Miners have cancelled sales in diamond trading hubs such as Antwerp and scaled back operations in South Africa and Canada. Retailers worldwide have been forced to shut their shops.

The lack of cash flow threatens a wave of defaults across the diamond supply chain if lockdowns continue into the summer.

“Many of the marginal operations hanging in there will be wiped out,” said Clifford Elphick, chief executive of London-listed Gem Diamonds. “When the tide recedes you see who is swimming without a costume, as Warren Buffett said.”

Prices for rough diamonds dropped 15 per cent to 20 per cent last month and are likely to fall further when bigger miners such as De Beers and Alrosa inevitably cut prices, according to Paul Zimnisky, a New York-based diamond analyst.

“A lot of these companies were having difficult times before this happened,” he said. “You’re going to see some restructurings at this point, how many can miss two or three or four sales events and continue?”

One weaker miner is London-listed Petra Diamonds, which operates in South Africa and Tanzania. The company’s shares have fallen 70 per cent this year amid worries over $650m in debt repayments due in 2022, giving it a market capitalisation of just £23m.

Petra said last month it had hired Rothschild to look at “strategic options” in relation to the maturity of its debt. The company declined to comment on its talks with bondholders.

Concerns are also growing about the solvency of India’s relatively unorganised diamond sector, where a few large cutters are joined by a myriad of small workshops operating with thin profit margins and high working capital needs.

Since the lockdown started “we’ve worried about what is the future of the industry”, said Shantibhai Patel, a jeweller in Gujarat who deals in diamonds. “When this type of situation comes it is hard to survive. Only necessary items will have a market. And we don’t have a market.”

India has steadily muscled out competitors such as China to dominate the global diamond manufacturing trade, importing almost $20bn worth of rough diamonds a year.

But it was at the heart of an international scandal in early 2018 when Nirav Modi, a flamboyant jeweller known for his celebrity clients, fled the country after being accused of defrauding a state bank of about $2bn.

Mr Modi, who denies the charges, is now in a London prison fighting extradition to India.

The alleged fraud prompted Indian banks to cut their lending to the industry but they still have considerable exposure. Concerns about the repercussions of a wave of defaults on India’s financial system last month prompted the Reserve Bank of India to announce a three-month moratorium on loan repayments for banks.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced on Tuesday that the lockdown, which was slated to end this week, would continue until May 3. Indian diamantaires expect the pain to last far longer.

“There is no demand. No retailers are going to order for a foreseeable period of time,” said one executive at a large Indian diamond group. “There’s no point buying it or manufacturing it if you see the world is not going to buy it . . . The more this drags on the more it becomes harder to sustain.”

Some diamond mining executives said the enforced isolation of billions of people could create pent-up demand once restrictions are rolled back and jewellery stores reopen. Jane Kozenko, a spokesperson for Alrosa, the world’s largest diamond miner, said many couples could make a decision on marrying after being confined together.

But Sanjay Shah, whose company KBS is one of India’s largest diamond jewellery manufacturers, said he expected any recovery to be slow. “We’re not dealing in bread or milk. We’re dealing with an item which is not an essential item to buy,” he said. “The demand will be more than a year and a half or two years from now.”

How Surat became the world’s diamond manufacturing hub

Diamonds are believed to have been discovered in India, with the global trade beginning about 1,000 years ago as the precious stones were transported through the Arabian peninsula and on to Europe.

The Koh-i-Noor, perhaps the world’s most famous, was from India and is now part of the British crown jewels.

By the 18th century, India’s diamond supplies were largely exhausted and the global trade shifted westward to new supplies in South America and Africa.

In recent decades India has reclaimed its place at the core of the diamond trade, not as a miner but the place where about 90 per cent of the world’s rough stones are cut and polished before being set into jewellery and sold around the world.

At the heart of this trade is Surat, an otherwise unremarkable city of about 4m people in the western Indian state of Gujarat.

Thanks in part to the diamond trade, Surat’s economy has boomed. Before the coronavirus pandemic struck, it was expected to be the world’s fastest-growing city by gross domestic product over the next 15 years, according to Oxford Economics, averaging 9 per cent a year.

The Indian cutting business started growing in the 1970s, thanks to communities of skilled workers in the regions surrounding Surat. From there it has steadily gained market share over previous hubs such as Antwerp or New York.

The shift was largely down to India’s labour advantage. It costs about $10 a carat to cut a diamond in India, according to consultancy Bain, compared with roughly $70 in Belgium and more than $100 in the US.

The industry now employs an estimated 700,000 workers, according to the Surat Diamond Association, many in workshops of a few dozen workers.

But its resilience is being tested by India’s lockdown. With many of those workers having left the city, diamond dealers say restarting operations will not be easy.

“If my workers have gone away, I have to bring them, I have to call them once the demand restarts,” said Sanjay Shah of KBS, one of India’s largest diamond jewellery manufacturers. “Once you shut everything, you have to rebuild. It’s a process.”