Dollar surge stirs talk of multilateral move to weaken it

A sharp rise in the US dollar during the coronavirus crisis could prompt an international intervention to pull it lower for the first time in 35 years, analysts say.

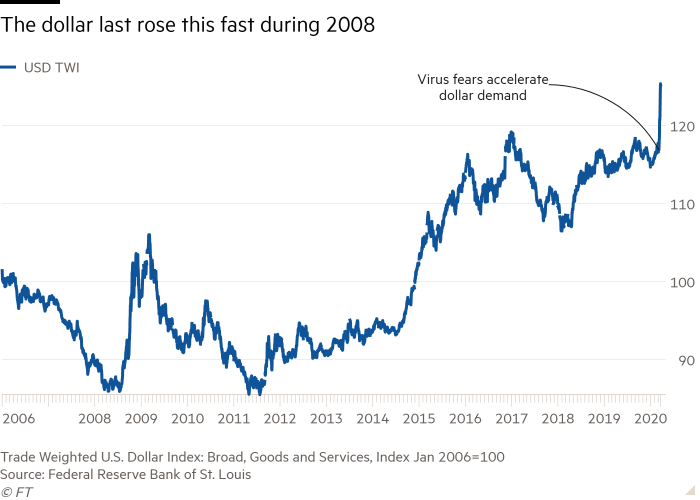

A scramble for dollars among companies suffering a collapse in revenues has helped to generate an 8 per cent rally in the trade-weighted dollar since March 9, which represents the currency’s sharpest increase since 2008. A hunt among investors for shelters from the market ructions has also helped to propel the dollar higher.

This is a boon for funds that have bet on a stronger dollar. But it is painful for governments and companies that have borrowed in dollars, pushing up the cost of repaying these debts. A strong dollar could also hamper US economic growth, which is already struggling under the weight of coronavirus. Agreements among major central banks to boost the supply of dollars around the global financial system with swap lines have helped only marginally. To ease the strain, said analysts, authorities might consider the first effort to push the dollar lower since the Plaza Accord of 1985.

“Should dollar appreciation continue, we would see a reasonably strong case for targeted intervention, and think there is a rising probability that authorities will take this step,” wrote Zach Pandl, Goldman Sachs foreign exchange strategist, in a note to clients. “If swap lines and [bond purchases] prove insufficient, we think Fed and Treasury should and will consider traditional FX intervention to stabilise the dollar.”

Some of the upward pressure on the dollar has faded in recent days. The currency weakened after the US central bank on Monday committed to unlimited purchases of assets — a step that has eased market stresses and allowed the dollar to pull back. But currencies like the Australian dollar and the pound remain about 9 per cent weaker than at the start of the month. The Mexican peso lost 28 per cent in March while the Brazilian currency slipped to record lows, losing 13 per cent this month. That has pushed up the cost of servicing huge amounts of dollar-denominated debt, just as the world appears to be on the brink of recession.

Talk of intervention in the dollar flared up in July last year, when US president Donald Trump repeatedly called for a weaker currency. At the time, analysts were doubtful that the Federal Reserve would agree to join a mostly politically-motivated assault on the dollar and intervene alongside the Treasury, while other central banks had little incentive to contemplate helping to push the US currency lower.

“I think this time the Treasury would get buy-in from the Fed, whereas last year that wouldn’t have been the case,” said Paul Robson, head of currency strategy at NatWest Markets in London.

“I think we are gradually getting to a place where co-ordinated intervention becomes a possibility,” he added. “The surge and scramble for the dollar makes this much more likely than six months ago.”

Multilateral currency-market interventions are rare. Since 1995 central banks have staged joint actions in currency markets just three times, including a concerted drive to weaken the yen after the devastating earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. The last time central banks combined to sell the dollar in an effort to push it lower was in 1985.

“Given the unprecedented deterioration in FX market conditions in some currency pairs, we would not dismiss the possibility of FX market intervention, in order to supply dollars and backstop FX market liquidity conditions,” said analysts at JPMorgan.