How Vitol was blindsided by the oil price plunge

Vitol chief executive Russell Hardy was in a buoyant mood in February. Oil prices had slumped as the coronavirus outbreak hammered fuel demand in China, but crude had started to recover as the disease appeared to be under control.

The London-headquartered company, which is the world’s largest independent oil trader, was coming off a near-record year in 2019 when it posted net income of $2.2bn, according to bankers who have seen the privately held company’s results.

“The expectation of the market today is it’s not going to get significantly worse than what we’ve seen,” Mr Hardy, 54, told Bloomberg TV on February 21.

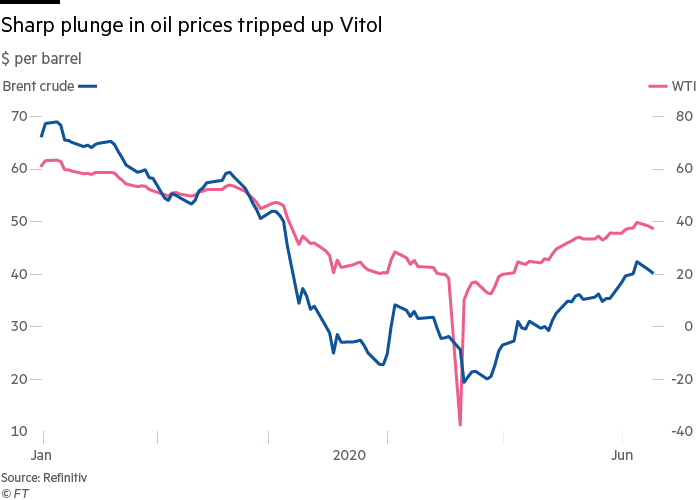

What happened next is well documented: outbreaks started to spread in Europe and by the middle of March countries around the world were locking down to ward off the pandemic. Global oil demand would fall by as much as a third, sending prices plummeting.

Vitol has a reputation for being one of the best-run trading houses, making money whether oil prices go up or down. But its fate shows how even the shrewdest companies were blindsided by the Covid-19 crisis. According to interviews with multiple traders close to Vitol employees, the company endured an unusually severe test and was forced to reorient its business.

Vitol’s net income plunged 70 per cent in the first quarter to $180m, according to figures seen by the Financial Times — a far cry from the $600m the company made in the same period a year earlier.

The company declined to comment.

Vitol trades between 7m and 8m barrels a day of oil and refined fuels, the equivalent of the combined consumption of the UK, Germany, France, Italy and Spain. In addition to its core physical business, the company also takes on speculative financial positions.

Yaoyao Liu, a Cambridge graduate known as a derivatives whizz-kid in the tight-knit oil trading community, is said by three rivals to have established a position betting on a recovery in oil.

The Vitol partner is said to have believed that China’s experience showed that governments could quickly get the virus under control and oil demand — and prices — would then rebound.

The bet went sour.

First, a large outbreak in northern Italy spooked investors. Then Russia and Saudi Arabia fell out over how the Opec+ group should respond to the rising threat to demand. That led to a fierce price war that saw Riyadh increase supply and offer crude at huge discounts.

Crude plunged from about $58 a barrel in late February to $25 by mid-March, leaving Mr Liu’s positions in the red.

Bankers briefed on Vitol’s business say the company had started the year holding a relatively large amount of oil as inventory, in anticipation of strong demand in 2020. While Vitol routinely hedges its physical positions, violent swings can make these trades imperfect.

The exact hit Vitol took is unclear. An email from a headhunter went to a rival trading house claiming that Vitol had suffered a loss as large as $1.6bn — a number that rapidly spread through the industry.

Vitol demanded a retraction and got one. People familiar with the matter say the alleged loss was heavily exaggerated.

But the fact the rumour was taken seriously shows how fraught a time it was. Vitol held a series of meetings with its financiers and counterparties, including banks and oil producers. The move to reassure partners was seen as notable by those involved in the meetings given Vitol’s size — it was estimated by analysts to be worth about $20bn in 2017 — and its record of profitability.

As demand plummeted, the company was forced to rearrange shipments to buyers in Asia that wished to delay taking fuel. Shipping rates also soared as Saudi Arabia tried to snap up almost every available tanker as part of its price war. The biggest fear within the company was buyers reneging on their contracts entirely, though ultimately few did.

At the depths of the crisis Vitol started looking for opportunities. It added to its vast global network of onshore storage, renting more space and snapping up cheap barrels for sale later, once prices recovered. In Iraqi Kurdistan, the company was getting oil for low single-digits under its cash-for-crude loans with the semi-autonomous state.

By late April, oil prices were at their lowest level in 20 years. Vitol is said by three rivals to have done well in the week US oil prices fell into negative territory as the market looked at the risk of running out of storage. After Saudi Arabia and Russia called a truce in their price war, Vitol snapped up more vessels for storing oil at sea — a traditional money-spinner for trading houses when markets are weak.

Vitol then called the bottom of the market, according to rivals, calculating correctly that US producers would be forced to curtail supply just as demand from motorists and industry started to pick up.

Oil prices have since rallied to about $40 a barrel. Some company insiders say it could even turn out to be a bumper year, given that traders typically prosper when oil markets are oversupplied.

“The mist is becoming a little clearer,” Mr Hardy told Reuters early last month. “It’s a bit easier to see the future.”