Market ructions test faith in classic portfolio mix

One of the basic rules of investment is coming unstuck, forcing some fund managers to rethink how they build their portfolios.

For much of the past century, the building blocks of most investment portfolios have been a combination of riskier stocks and steadier, safer bonds. Like a see-saw, one typically rises if the other falls, smoothing returns and offering a hedge.

But over the past decade, this relationship has broken down. Bond yields have sagged as their prices have risen alongside equities, producing healthy gains but limiting how much protection bonds can offer in downturns. The recent market chaos unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic has underscored the problem, with bruising trading periods in which bonds and equities have dropped in unison.

“This is the biggest story for institutional investors right now,” said Paul Britton, the head of Capstone, a New York hedge fund. “You could always sleep at night knowing that bonds would protect your portfolio — and paid you for doing so — but you’re now at the mercy of the gods.”

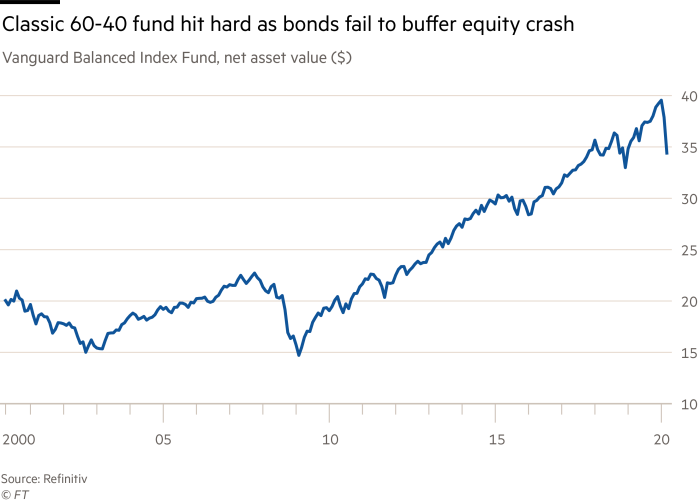

The classic balanced portfolio consists of 60 per cent stocks and 40 per cent bonds. Variants on this basic construction are popular with everyone from big pension funds to retail investors, thanks to the steadiness of its returns compared with less diverse, riskier portfolios.

Since the financial crisis, this strategy has performed well as both key components have strengthened. A US 60-40 portfolio in the decade to 2020 produced its highest volatility-adjusted returns in over a century, according to investment bank Goldman Sachs. But in the first three months of this year, the 60-40 strategy suffered one of its worst performances since the 1960s, as the bond rally proved insufficient to offset the tumble in stocks.

Goldman now warns that the longer-term outlook is for lower returns and “larger and more frequent drawdowns” for the once-trusty 60-40 portfolio. “Balanced portfolios have become more risky,” Christian Mueller-Glissmann, a strategist at the bank, warned in a recent report.

Investors are now grappling with the implications. In Bank of America’s investor survey in March 52 per cent of fund managers said that US government bonds were the best hedge against turmoil. That share dropped to 22 per cent in April.

Gold saw the biggest rise in popularity, helped by its strong recent performance. But it is not a big enough asset class to offer enough protection for the trillions of dollars managed by big institutional investors.

The most popular hedging alternative in the BofA survey is now put options. These are derivatives that act a bit like an insurance policy, by offering buyers the chance to sell stocks at a pre-agreed price in return for a steady premium.

However, at the moment, these puts are extremely expensive. Although stocks have enjoyed a strong rebound, investors remain nervy, and buying puts is akin to buying hurricane insurance after a storm has already struck. This means that premiums are unusually high even for those heavily “out-of-the-money” puts that pay out only in the case of another savage drop.

In the longer run, some analysts and fund managers expect broader derivatives-based strategies to become more popular among institutional investors that want to insulate their portfolios against big falls.

The best example are “tail risk” funds, which collect a steady stream of payments from institutional investors in return for insuring a certain amount of their equity exposure. Many tail risk funds clocked huge gains last month.

But the problem with tail risk funds is that such protection does not come cheaply. Paying fees to an investment manager year after year with often little to show for it makes them hard to hold on to — as Calpers, the US pension fund, demonstrated by ditching its tail risk fund allocations in January 2020.

“Tail risk funds do the job, but they come at a cost,” said Capstone’s Mr Britton, whose fund manages a tail risk strategy. “People just have to accept that they have to spend more money on tail risk hedges and lower their return expectations.”

Not everyone is convinced that such expensive strategies are a feasible alternative for big institutional investors.

“There’s not nearly enough liquidity in those strategies to make them remotely viable for big investors,” said Mark Wiseman, formerly head of active equities at BlackRock and one-time chief executive of CPPIB, a big Canadian pension fund. “You just get some expensive, short-term performance-smoothing in return for a worse longer-term performance.”

Mr Wiseman argues that most truly longer-term investors should simply increase their equity exposure and add riskier strategies to make up for the fact that future fixed-income returns are now expected to be lower. Overall returns will be more volatile as a result, but for those that can afford to ride through it, the outcomes will be better.

“There is no real alternative to fixed income,” Mr Wiseman added. “Maybe the answer is simply to hold more equities, and hold on tight.”