State-backed rally draws Chinese investors into ‘fickle’ stocks

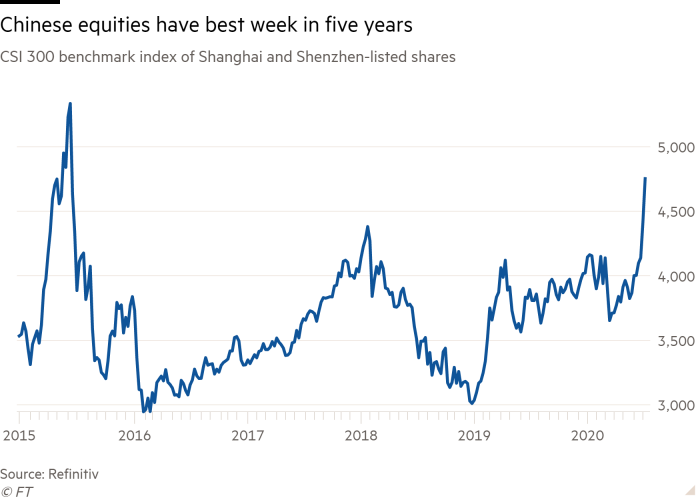

Chinese equities have enjoyed their best week in five years as legions of the country’s retail investors rushed to participate in a booming stock market.

A gauge of the country’s 300 biggest Shanghai and Shenzhen-listed stocks, which saw a run of eight consecutive days of increases end on Friday, is up 16 per cent so far this year, while benchmark indices in the US and Europe remain stuck in negative territory.

Analysts said an air of euphoria has descended on the market, reflecting a widely held belief that rising prices are sanctioned by the state and that any dips will not last.

“It’s not over yet,” said 29-year-old Mr Ji, who works in the investment industry in Shenzhen. He said he had made a return of more than 40 per cent on the hundreds of thousands of renminbi he had invested since February, and planned to buy more. “The attitude of the government implies it expects a lasting bull market.”

State-media endorsements of a “healthy” bull market on Monday appeared to signal official support for the rally, which has emerged as China strives to shake off the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic after its first quarterly fall in output in more than four decades.

The pace of this week’s gains conjured memories of a bubble in 2015, when prices, spurred on by the state, rose and then collapsed in spectacular fashion.

Back then, “if you asked anyone why they were in the market, they all gave the same answer, which is that the government wants the market to go up”, said Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University. He added that the 2015 boom also came at a time when growth and corporate profits were fading.

Ms Zhang, an office worker in Beijing in her thirties, said she lost about a fifth of her investment in the bust of 2015. But the recent rally had pushed her into positive territory once more.

“I made a profit of 15 per cent and then quickly sold out of the market,” she said. “I want to wait and see if there’s an opportunity to get in [again], but I’ll be more cautious this time.”

Chaoping Zhu, Shanghai-based global market strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management, said that shutdowns and fears over jobs had led households to increase their savings, which might now be feeding into the markets. He pointed to data from the People’s Bank of China, which show household deposits rising to Rmb88tn ($12.6tn) at the start of May, compared with less than Rmb82tn in December.

“Households have a lot of money in their hands, and they are struggling to find a good place to put that money,” he said. He added that returns on wealth management products had fallen this year, against a backdrop of monetary easing and a slew of defaults.

An official at the Shanghai Stock Exchange, who is not allowed buy shares directly because of compliance requirements but does not want to miss out, said he had invested in mutual funds that buy brokerage stocks. He is up 40 per cent in a week.

He added, however, that corporate profits need to improve or the “rally will disappear as fast as it emerges”.

Cao Shuping, a 50-year-old retiree from Shanghai, said she made about 10 per cent this week, but was not convinced that bullish conditions would continue. She said she would rather dip in and out, “just to earn some pocket money”.

Some of that sense of restraint is coming from editorials in state media, which are often taken as a reflection of the will of the government. After Monday’s cheerleading, the China Securities Journal appeared to backtrack on Thursday, referring to the “tragic lesson” of stock market volatility five years ago.

Elsewhere on Thursday, the country’s securities regulator published a list of 258 platforms that were illegally offering margin finance. Overall, the official amount of borrowed money in the market has risen to its highest level since 2015, but remains well below the peak that year.

Much of the excitement for stocks is being stirred up on social media platforms, which Mr Zhu of JPMorgan said played “a very important role in driving psychological mania for the market”.

On apps such as WeChat and Weibo, analysis of stock moves competes with official financial media for attention. One owner of a Weibo account with 680,000 followers this week described a friend who started to trade because he had a lot of spare money and saw no other routes to invest.

“The real question,” the post asked, “is why the market suddenly became bullish”. Last month people did not seem too optimistic, but now they have changed direction.

“It’s just too, too fickle,” the author wrote.