Turkey digs in for currency battle

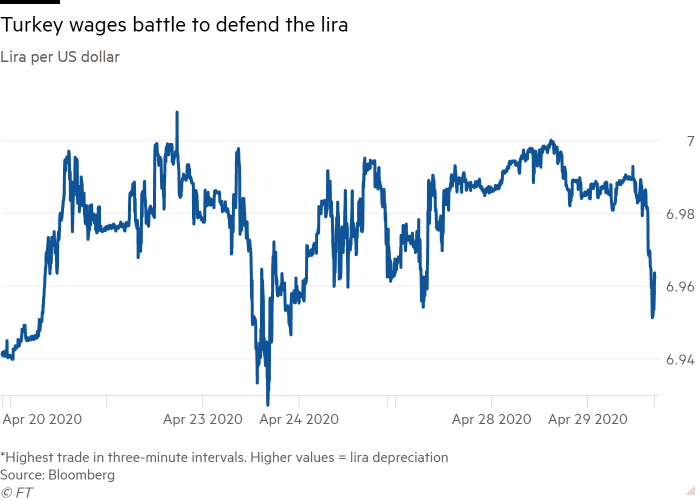

The Turkish lira looks like it has been fairly steady in recent days, but behind the scenes a battle is raging to hold it up against the US dollar.

Like many emerging-market currencies, the lira has crumbled under the strain of coronavirus and the large interest-rate cuts that policymakers have launched to support the economy.

But for more than a week, every time the dollar has threatened to break above 7 to the lira — a level last seen in the country’s 2018 currency crisis — it has been pushed back down again under a wave of dollar selling.

“It’s actually quite interesting seeing someone trying to give two fingers to economic or financial logic,” said one foreign fund manager, who asked not to be named. “They’re really digging themselves quite a decent hole.”

The country’s foreign currency reserves have plummeted since the start of 2020. Gross reserves, including gold, have fallen more than $17bn this year to under $88bn.

The consensus among economists and investors is that the drain in reserves is the result of the central bank using its war chest to fund intervention in the supposedly free-floating currency.

“Ever since 2015, you’ve had these episodes where, as soon as lira goes close to 3, or 4, or 6 or 7, you have this little cat-and-mouse game,” said Erik Meyersson, a senior economist at the Swedish bank Handelsbanken. “Every time this happens, you see that the reserves start to slide.”

Turkey’s central bank governor, Murat Uysal, on Thursday denied that it was seeking to defend a specific level for the lira. “We can very clearly see that this is not the case,” he told a press conference, pointing to the slide in the currency since March. He said the “volatility” in the bank’s foreign currency reserves was “very normal” and also “temporary”.

Nonetheless, the tussle around 7 persists. Traders say that on one side of the struggle is the central bank and state-owned lenders that have been selling dollars on its behalf each time the lira has slid towards that level.

On the other is a broad mix of lira sellers, from Turkish households and businesses to foreign investors, which either want to sell lira or get their hands on dollars.

Paul McNamara, an investment director at the asset manager GAM, said a reason for lira weakness was a surge in domestic demand for dollars and for overseas goods, caused by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent drive for credit-fuelled economic growth. “We’ve always seen that, when the government pushes up credit growth, that quickly feeds through into higher imports, which put pressure on the current account,” he said.

At the same time, concern about the coronavirus pandemic has triggered a broader flight to safety by international investors, who have pulled billions of dollars out of emerging markets.

The exodus has been compounded by an aggressive series of rate cuts despite the country’s high inflation. Another factor is the Turkish central bank’s recent decision to accelerate a bond-buying programme. Goldman Sachs and others have warned that this has increased the supply of lira, risking further pressure on the currency.

Turkey’s leadership is eager to stop the lira from sliding. Ordinary Turks tend to view the currency as a barometer of economic health, while Mr Erdogan has frequently railed against anyone betting on its decline. A stable lira is also important to Turkish companies that are loaded up with foreign currency debt.

But Atilla Yesilada, an Istanbul-based analyst at the consultancy GlobalSource Partners, questioned the logic behind burning through precious reserves to protect a psychological threshold. “What is so magical about 7?” he asked. “What about 6.90 or 7.10?”

“I don’t disagree with the government that the currency is important, but this is like curing the symptoms,” he added. “It doesn’t cure the disease.”

The pressure on the currency has a familiar feel for seasoned Turkey watchers, who have seen the country go through multiple cycles of aggressive rate cutting and currency depreciation, before the central bank was forced to dramatically raise interest rates.

Following last week’s rate cut, TD Securities predicted that the central bank would have to adopt “aggressive tightening when all local resources and measures prove ineffective against continued lira weakness”.

Daniel Grana, head of emerging markets at the asset manager Janus Henderson, said Turkey would at some point either have to “let the currency go” or take short-term swap lines from the IMF.

Even the latter would be a temporary solution, he added, while noting that Mr Erdogan — who has repeatedly ruled out turning to the IMF — would be unlikely to agree to a full package from the international lender. “The key question now is what the locals will do,” Mr Grana said. “If they take fright, that could be a catalyst for a currency crisis.”

That is why some investors have begun to speculate that the government could take the once-unthinkable step of imposing capital controls — although it has ruled out such a move in the past.

Charles Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, an investment bank, said: “The trouble is that there are so many measures a government can take, from seizing corporate and household currency deposits to suppressing demand and delaying projects, that it is possible to hold down a currency much longer than is economically sensible.”