Why the Fed is trying to tame the dollar

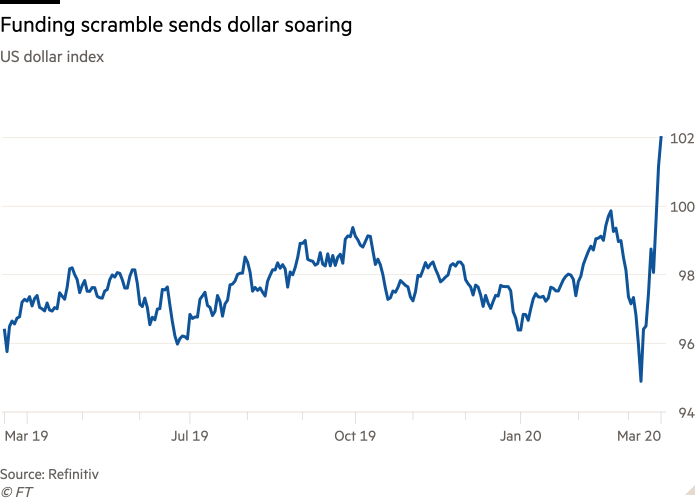

The dollar has blasted higher since the coronavirus crisis in markets intensified, hitting a record high when compared with a trade-weighted basket of other currencies this week.

The Federal Reserve has stepped in by opening dollar swap lines with other central banks — measures it extended to a wider group of other central banks, including some in emerging markets, on Thursday. The aim is to stop stress in dollar markets from spiralling out of control and spreading the strain through the financial system.

Here is a guide to what is going on and why it matters.

Why is the dollar strengthening?

Investors tend to buy dollars during times of geopolitical uncertainty and financial market stress, given that it is viewed as the key global haven.

Just as families stock up on staples to avoid running out during uncertain times, investors and companies, as well as banks and hedge funds, are scrambling for dollars to get through the slowdown. This sudden demand has made it more expensive to buy the dollar outside of the US, while the rush to buy the currency has led to problems with availability.

Since the beginning of the month, equity markets have plummeted and vital debt markets, including those for US Treasuries and mortgages, have started to fray, along with short-term funding markets. Policymakers have taken steps to address these issues, but at times, equities and bonds have been dropping simultaneously — a classic sign of market distress.

This prompts companies, for example, to bulk up on dollars to make up for lost revenues.

“People are craving the most secure asset they can find, and that is the dollar. People are hoarding dollars. Banks are hoarding dollars,” said Nick Maroutsos, co-head of global bonds at Janus Henderson. “There really isn’t anywhere to hide. People are coming to the realisation that you have to be as defensive as possible, meaning you hold cash and some assets when you can.”

Is this a problem?

The dollar is the world’s main reserve and payments currency, meaning it is the currency in which most global trade and investment takes place.

The overall size of global liabilities denominated in the US dollar stands at $12tn or 60 per cent of US gross domestic product, according to JPMorgan analysts. That means a lot of companies and governments now have dollar debts to pay at a time when revenues are collapsing and economies are grinding to a halt.

The pressure had cropped up in one metric of dollar demand: cross-currency basis swap spreads. These spreads track the premium that market participants pay to swap one currency for another. Earlier this week, the three-month cross-currency basis between the euro and dollar soared to its widest level since 2011, suggesting investors were willing to pay about twice as much to borrow the greenback against the euro than they were just a few days before. Investors seeking to swap Japanese yen also faced steep costs to secure dollars.

“Just as no part of the global economy will be insulated from the impact of the virus, no major part of the global economy will be insulated if dollar funding markets break down,” said Brad Setser, an international economist at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Should that happen, Mark McCormick, global head of foreign exchange strategy at TD Securities, said the liquidity problem could turn into a solvency issue. “The [US dollar] sits at the epicentre of that, and its strength reflects a mismatch of supply and demand for funding.”

What has the Fed done?

The US central bank had already set up dollar swap lines with the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and Bank of England when the coronavirus crisis bit seriously into markets. The move means it can provide dollars directly to local central banks in exchange for local currency, in a bid to increase the availability of dollars in those local markets.

That did not stop the rally, however, with the buck continuing to rip into currencies including sterling, the Australian dollar and a range of Asian currencies. Now, the Fed has added nine more countries, including Australia, Brazil and Mexico, to the list.

The aim is to prevent funding pressures from evolving into a full-blown crisis.

“These facilities, like those already established between the Federal Reserve and other central banks, are designed to help lessen strains in global US dollar funding markets, thereby mitigating the effects of these strains on the supply of credit to households and businesses, both domestically and abroad,” the Fed said in a statement.

This has happened before. During the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed extended the swap lines to all G10 countries and a handful of emerging market economies, including Brazil, Mexico, South Korea and Singapore.

Will it work?

According to Calvin Tse, head of North American forex strategy at Citigroup, the first round of forex swaps had a “large effect” in the countries where the swap lines were deployed. “Barring another shock, the worst of the cross-currency basis widening for those countries may be behind us,” he said.

However, dollar funding costs remain high for others without this access. In addition, these are temporary backstops, and for dollar funding pressures to abate altogether, Mr Tse said a sense of normality had to return to financial markets.

“As long as there remains volatility and concerns on growth and health, which then weigh on credit, it will keep feeding on itself,” he said.

Are you seeing job cuts happen in your workplace or others? Is your company discussing changes in pay or benefits? Tell us what you’re seeing. Send tips and stories to coronavirus@ft.com.