How bank hedging jolted investors into talk of negative rates

Hedging by some of the biggest banks in the US last week sparked a flurry of concern that the Federal Reserve could cut interest rates below zero for the first time, senior traders say.

Despite months of pushback from the Fed, rates on so-called fed funds futures contracts — key tools for investors seeking to bet on or hedge against interest-rate shifts — popped above 100 last week. That signalled an expectation among traders that negative policy rates were on their way for the first time in US history.

The unprecedented pricing quirk prompted immediate rebuttals from Fed officials, with several including chairman Jay Powell dousing down the notion of negative rates in the following days.

But senior traders active in the market say few funds or banks are betting on the Fed following peers in Europe or Japan into negative rates. Instead, some banks are trying to protect themselves and their clients against this high-stakes tail risk, they say. In a vicious cycle, the more hedging that goes through the market, the stronger those expectations for negative rates become.

“These fed funds futures markets are not that deep,” said Blake Gwinn, head of short-term rates strategy at NatWest Markets — one of the elite group of 24 primary dealer banks that serve as trading counterparties with the Fed.

“If one or two large banks say they will execute these hedges, that is enough to start pushing things. Once that started, it fuelled a whole conversation about negative rates,” he said. “Within hours I was getting phone calls from clients about if we were going to go negative.”

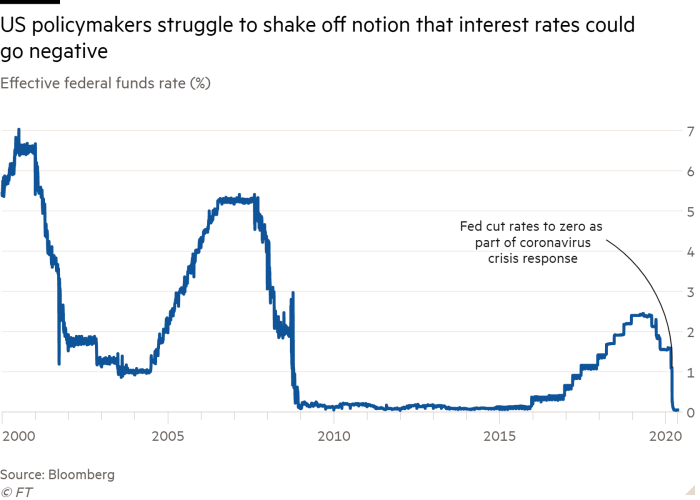

The Fed is struggling to shake off the notion that rates, which already hover close to zero, could turn negative, imposing a cost on deposits in the hope of forcing money into other riskier ventures. US president Donald Trump is a vocal advocate of negative rates, describing them as “a gift” to an economy struggling under the weight of coronavirus.

Mr Powell reiterated on Wednesday that it was not something the central bank was considering, echoing statements from other senior Fed officials. Central banks that have used them, in the eurozone, Sweden, Switzerland and elsewhere, have struggled to contain the backlash against them from banks and savers.

Nonetheless, fed funds futures contracts expiring between March 2021 and March 2022 still implied sub-zero US rates on Wednesday and Thursday. At 100.03, the July 2021 contract implied a policy rate of -0.03 per cent on Thursday. It traded as high as 100.065 on May 8.

This stems in part from swaps contracts — tools that Wall Street banks provide to companies, enabling those clients to swap a stream of floating rate payments for a fixed rate to shield them from volatility in benchmark interest rates.

But the hedges have a hitch. If market rates stumble below zero, the company expecting to receive a floating rate payment would instead have to pay the bank. To reduce that risk, they ask their banks for floor swaps that set a limit at zero. Some companies that did not already have limits in place entered into new transactions to hedge themselves in recent weeks.

While the banks are happy to oblige, they must also hedge themselves. They do so by buying fed funds or other related products, pushing their prices higher.

Some banks were inundated last week with corporate clients seeking out floors on their initial swap agreements, given short-term rates were closing in on zero. The move towards zero also meant banks were caught wrongfooted on swap contracts including floors that they had agreed to months or years beforehand, prompting those dealers to hedge further.

Adding to the pressure, some primary dealers received requests from other banks trying to hedge their portfolio of loans just in case the Fed reversed course on its stance. One dealer also said large hedge funds were placing bets that rates would turn negative.

“Banks have trillions of dollars of loans on their books. There would be nervous [bankers] across the world for sure,” said a senior fixed income trader at one primary dealer bank. “If you really trust the Fed and [your] economist, but the president is saying another thing . . . let’s go hedge 10 per cent of our book.”

Investors and analysts are unwilling to rule out the possibility of negative rates, despite the Fed’s assurances, especially in light of the other extraordinary steps the central bank has taken to dull the blow of coronavirus. Aaron Liebhaber, the interim head of US institutional rates sales at RBC Capital Markets, another of the Fed’s primary dealers, was among those who saw dealers hedge against negative rates last week. He said more of the bank’s clients were now seeing negative rates as “a growing, if still unlikely, possibility”.

“In a world where central banks are increasingly willing to entertain unconventional ideas, it is a mistake to believe that the distribution of outcomes doesn’t include things that weren’t previously possible,” added Bob Miller, BlackRock’s head of fundamental fixed income for the Americas.

Investors such as Mr Miller point to the Fed’s unprecedented decision to lend support to the markets for municipal debt and corporate bonds — including those issued by riskier borrowers. The measures, as well as the US central bank’s pledge to buy an unlimited quantity of government debt, go far beyond what it was willing to do during the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

“You can imagine that there are a number of investors who have been shocked by this dramatic change in the interest rate environment in just a three-month period and are now willing to spend money on insurance premiums with the expressed hope that those insurance policies are never necessary,” he said.